Humans have always been attracted to blue spaces. Early humans needed places with water for their physiological health. Homo sapiens urbanus now rely on blue spaces more for their psychological health, to provide relief from their Red Mind. Red Mind is a state of heightened stress and anxiety often associated with sensory overload in urban environments from traffic, crowding, noise pollution, light pollution, social media, and intense heat. These urban stresses have degraded our wellbeing to the point that we are in a mental health crisis.[1] The antidote to Red Mind is Blue Mind, the mildly meditative state people fall into when they are in or near water. The Blue Mind theory and movement was popularized by Wallace J. Nichols in his book Blue Mind.

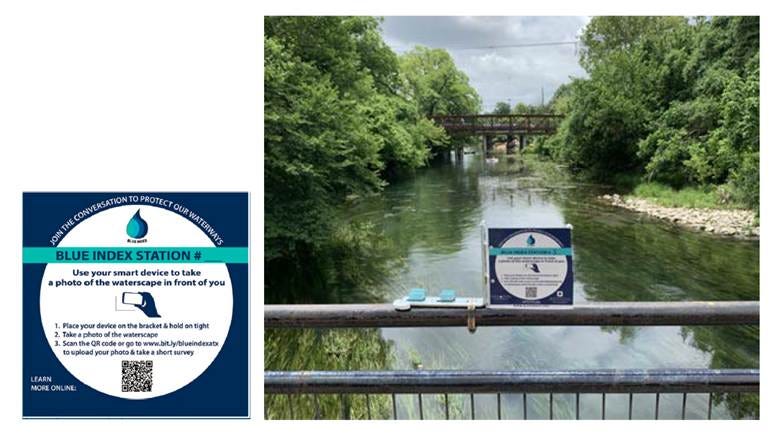

Blue Mind has been an inspiration for my work on the San Marcos River social-ecological system (see last week’s post). It has also been inspirational for my students, one in particular. Madeline Wade earned a B.A. in Psychology and a B.S in Environmental Studies from the University of Oklahoma. This double-major served her well for her master’s studies with me at Texas State University. One of the first assignments I gave her was to read Blue Mind, which sparked an idea for her thesis research on the San Marcos River. Her plan was to interview river users and study how they connected with this blue space. But then COVID-19 shut down the river parks and prevented her from conducting face-to-face interviews. We had to call an audible and come up with another plan of attack. How could we collect information on people’s connections to the river? The answer was Blue Index. Blue Index is a concept that was envisioned by Wallace J. Nichols, but put into action and advanced by Kevin Jeffery and Sarah Davidson. Kevin and Sarah developed a framework to quantify people's emotional connection to water bodies and then use that data to show decision-makers the value of investing in them. Madeline adopted their framework and methodology by installing 10 Blue Index photo stations around Spring Lake and along the San Marcos River. Each station consisted of an L-shaped frame and an acrylic sign with instructions for submitting photos and participating in the assessment.

Madeline’s Blue Index study of the San Marcos River collected 565 complete assessments, where each social actor submitted a waterscape photo and answered 18 questions about this blue space. Questions in the assessment consisted of (1) reported emotional experiences at the waterscape, (2) perceptions of waterscape characteristics including cleanliness, naturalness, accessibility, and flow, (3) perceptions of relaxation and refuge, (4) values based on which river function was deemed most important, (5) types of activity and frequency of visits, and (6) relationships with waterscapes before and after the onset of COVID-19. The full survey, results, and findings can be found here in our open-access article in the journal Land.[2] Most respondents (57%) indicated they spend more time at the river than they did before the onset of COVID-19. Moreover, 93% of respondents agreed that the waterscape they were visiting represented a refuge from stress and isolation caused by COVID-19. Overall, people valued waterscapes for ecological benefits and relationships with the place, rather than for recreation and tourism. Emotions experienced at all 10 waterscapes were overwhelmingly positive. Statistical tests revealed that higher positive emotions (Joy, Amazement, Serenity) were significantly associated with biophysical perceptions of flow, cleanliness, and naturalness. Below is a word cloud with all of the emotions, perceptions, and connections revealed by our Blue Index study of Spring Lake and the San Marcos River.

What our study demonstrated was that the benefits of blue spaces are influenced by visual biophysical characteristics but are also shaped by unseen emotional experiences. In sum, blue spaces have profound and measurable benefits to overall wellbeing, especially in urban settings where stressors are typically more intense and ubiquitous. Maintaining healthy blue spaces is a cost-effective way to mitigate negative mental health effects from these stressors. In central Texas, unique blue spaces are held in high regard and are seen as a symbol of the cultural, social, and environmental history of the region. I will explore this concept of place identity in next week’s post. For now, I want to stress the importance of participatory planning through community engagement and knowledge coproduction. I was delighted to see that the Spring Lake Vision Plan (May 2025) just released by Texas State University is designed around connections among nature, society, and history. I hope the City of San Marcos takes a similar approach in their vision plans for the Riverfront Parks and the Eastside Regional Park. If you have not already, I encourage you to share your input on the conceptual plans for these parks here. The deadline is June 15.

The purpose of this post was to bring awareness to the benefits of blue spaces, but it is also a homage to Wallace J. Nichols, who left us one year ago this week. In his words, “I wish you water.”

Sneak Peek of Next Week

Next week will be my final post about the San Marcos River, at least for a while. I will discuss mermaids and place identity.

Word of the Week

In honor of the great Blue Mind, Wallace J. Nichols, this week’s word is neuroconservation. From Openwaterpedia:

Neuroconservation is the new study, field, and science conceived and established by Dr. Wallace J. Nichols that raises awareness of the cognitive benefits of exposure to a clean, healthy nature. In so doing, human's natural neurological response can shift away from stress and towards hope and compassion. By including the cognitive benefits of nature in the broader discussion of ecosystem services and wildlife conservation, a more complete picture is generated in which the interests of humans and nature are aligned and intertwined. With this connection made, conservation is the meaningful course of action.

Below is my favorite public talk of Wallace J. Nichols and one I show in my courses. The title is Neuroconservation: your brain on nature.

Song of the Week

I cannot think of a more fitting song for this week’s topic and a perfect prelude for next week’s topic than the theme song for The Little Mermaid. The little crab, Sebastian, is big on wisdom:

The human world, it's a mess

Life under the sea

Is better than anything they got up there

Under the sea

Darling it's better

Down where it's wetter

Take it from me

Up on the shore they work all day

Out in the sun they slave away

While we devotin'

Full time to floatin'

Under the sea

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. 2024. Protecting the Nation’s Mental Health, https://www.cdc.gov/mental-health/about/what-cdc-is-doing.html.

[2] Wade MT, Julian JP, Jeffery KS, Davidson SM. 2023. A participatory approach to assess social demand and value of urban waterscapes: A case study in San Marcos, Texas, USA. Land 12(6), 1137, https://doi.org/10.3390/land12061137.