“The rice grass is growing too much. It makes the river look really gross and tacky.” This was a comment by a non-student resident of San Marcos, Texas when asked about their perception of the San Marcos River—a spring-fed river with cool, clear water that supports a diverse social-ecological system. Another San Marcos resident, this time a university student, commented that, “I think it’s pointless to keep weeds in the water. All to save some rice?? Sorry but I put humans needs over rice....” The weeds and rice grass these San Marcos residents refer to is the Texas wild rice—a protected plant that can only be found in the San Marcos River and that provides many ecosystem services including habitat and improved water quality. Both of these people said that they “greatly appreciate” the San Marcos River and its clear water. They appreciate it so much that they visit the river almost weekly and daily, respectively. They both also said that if the water quality became degraded, they would visit the river less often and not enjoy it as much. From these responses, it is crystal clear (clearer than the water in the San Marcos River) that these two people appreciate having a healthy blue space in which to recreate, but do not understand that the protected “rice grass” is the primary reason why this river is flowing with clean water.

The comments of these two river users, along with their responses to our 56-question survey, demonstrate relational values—those values that are embedded in the “preferences, principles, and virtues associated with relationships, both interpersonal and as articulated by policies and social norms.”[i] In other words, relational values manifest because of the relationship a person feels they have with the environment. Value is not necessarily found in the benefits they receive or the inherent functions of the environment, but rather in the connection between humans and nature. Relationships with nature might be valued because of certain goals, emotional factors, spiritual or cultural significance, or other interactive processes between humans and the ecosystem.

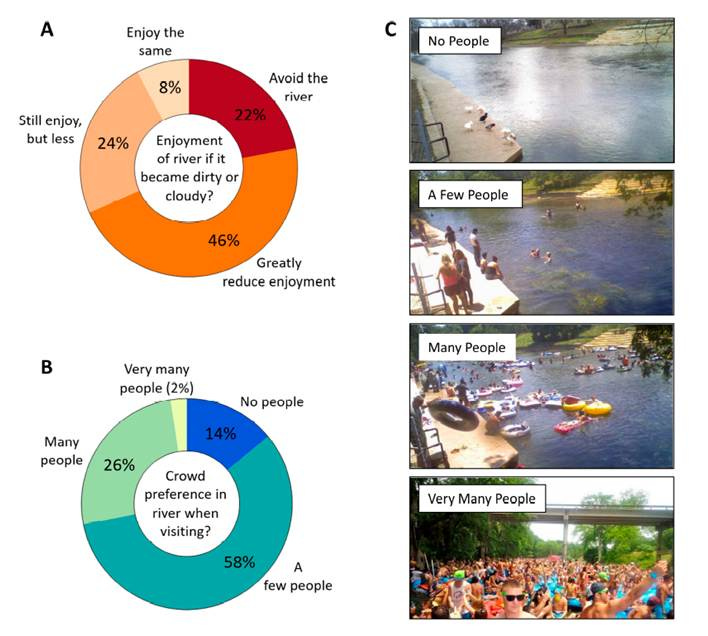

Using the San Marcos River as a case study, my research team and I investigated the spectrum of relational values that people have with blue spaces. The link to the journal article and our findings can be found here. A big shout out to the first author of this article, Christina Lopez, who helped synthesize and articulate concepts that I have been trying to organize for a decade. By analyzing different groups of visitors and affected parties (3,145 people in all), we found that the San Marcos River social-ecological system is a heavily used and highly valued resource, particularly for its clean water, natural habitat, and tranquil milieu. Indeed, most river users preferred only a few people when they visit and said that their use and enjoyment of the river would be greatly reduced (or they would avoid the river altogether) if the water became dirty or cloudy.

Our study’s findings were analogous to other social-ecological system studies from around the world in that different social actors interacted with their environment in different modes (see article for full results). In general, non-student residents visited the river weekly with a relatively small group and used the river parks for swimming, exercising, and socializing. Students visited the river much less (monthly or semi-monthly) and also used the river parks primarily for swimming, but floating (in an inner tube) and relaxing were their second and third most popular activities. Tourists mostly used the river a few times a year for floating, often with an alcoholic beverage cooler. While students and tourists used the river for alike activities and with similar frequency, a notable difference between the two social actors was that students placed significantly higher value on the cultural aspects of the river. The overall sum of social demand for the San Marcos River showed that people have preference for an ecologically healthy river that is swimmable and clean enough to float. A decline in any of those attributes could result in negative and likely unsustainable outcomes.

Unlike the two comments at the beginning of this post, the majority of survey participants (72%) prioritized environmental health over human use of the river. To further explore relational values, we asked participants to distribute money (percentage-wise, totaling 100%) from a hypothetical annual fund dedicated to improving the San Marcos River. The funding distributions were relatively consistent across all user groups (see figure below), with water quality protection, water quantity protection, and habitat protection being the top three funding priorities. Riverfront development for housing, dining, and shopping was by far the least important—less than 5% for all user groups. These results are timely because the City of San Marcos is in Phase 2 of developing a Vision Plan for its riverfront parks. From reviewing the different concept plans and talking to Parks staff, one of the objectives of the Vision Plan is to add more riverfront parking. Our study’s results show that while some people do want to increase river access, the vast majority of all social actors prioritize protecting the natural resource and ecosystem health.

The findings that I have presented here are just a few highlights from our decade-long study of the San Marcos River social-ecological system. My research team has produced a trilogy of publications from this study, which are listed below with links to the freely available journal articles. Given the amount of change that is occurring in our beloved town and our beloved river, I encourage you to share these resources with planners, decision-makers, and our community of good social actors. In closing, I want to share a few more comments from our survey that demonstrate relational values with blue spaces and are more representative of the community than the two comments at the beginning of this post:

“My days at the river usually involve just looking at it. I pick up trash every time I visit. Though I don't know much about it, I do know that it is a delicate place and would love to see it preserved as much as possible.” —Resident, non-student

“I’ve noticed in the past 43 years that as people become acquainted with our river, they develop an intimate desire to call it their own. Perhaps for its beauty and clarity, or ability to change your overall mood during the hot summers, but there is certainly something special about this river for each of us.”—Resident, non-student

“I think of jumping into the river for the first time as a "social baptism" - that's when a lot of people I know including myself kind of confirm that we've become Bobcats.” —Resident, student

Julian research team trilogy of San Marcos River studies:

Wade MT, Julian JP, Jeffery KS, Davidson SM. 2023. A participatory approach to assess social demand and value of urban waterscapes: A case study in San Marcos, Texas, USA. Land 12(6), 1137, https://doi.org/10.3390/land12061137.

Lopez CW, Wade MT, Julian JP. 2023. Nature-human relational models in a riverine social-ecological system: San Marcos River, Texas, USA. Geographies 3:197-245, https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies3020012.

Julian JP, Daly G, Weaver RC. 2018. University students’ social demand of a blue space and the influence of life experiences. Sustainability 10(9): 3178, https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093178.

Sneak Peek of Next Week

There were too many aspects of the San Marcos River social-ecological system to cover in one post. So next week, I will take another journey down this blue space to discuss emotional attachments and place identity.

Word of the Week

This week’s word comes from The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows by John Koenig. Koenig’s original dictionary focuses on “the language of emotion, vast holes in the lexicon that we don’t even know we’re missing.” One of these emotional expressions relevant to this week’s topic of relational values is:

Idlewild

adjective. feeling grateful to be stranded in a place where you can’t do much of anything [like floating down a river], which temporarily alleviates the burden of being able to do anything at any time and frees up your brain to do whatever it wants to do, even if it’s just to flicker your eyes across the passing landscape.

Idlewild was the original name of the New York International Airport, which opened in 1948. It was so named because it replaced the Idlewild Golf Course along the northeastern coast of Jamaica Bay. This impervious airport also replaced a large valuable blue space—a 5,200-acre coastal marsh ecosystem. Around the airport, you can find marsh remnants, a park preserve named Idlewild, and the Idlewild Environmental Science Learning Center, which “offers authentic, natural opportunities to learn and enjoy the unique ecological and cultural resources in Idlewild Park.” Idlewild Airport was renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport on December 24, 1963 to honor the president who was assassinated a month and two days before. JFK’s assassination resulted in the presidency of LBJ, whose two terms would have deep-rooted impacts on the nation’s connections among nature, society, and history.

Song of the Week

The last respondent comment in this week’s post about jumping into the river for the first time being a "social baptism" made me think of a song by one of my favorite artists and a fellow Texan. Leon Bridges wrote the song River to reflect the struggle he was having with depression. In his words,

I had little hope and couldn't see a road out of my reality. The only thing I could cling to in the midst of all that was my faith in God and my only path towards baptism was by way of the river.

[i] Chan, K.M., et al. (2016). Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 1462–1465.